Jack Kerouac - a Wandering Canadian?

par Harvey, Christian

Jack Kerouac, high priest of the Beat Generation and author of the celebrated novel On the Road, is a legendary figure of American literature for several generations of readers. While Kerouac’s work was first published in English, it drew inspiration from and is connected to the cultural heritage of French North America. The path of Kerouac’s life was determined in part by a childhood spent in a Petit Canada community in Massachusetts, where Kerouac was a Franco-American who used French frequently and fluently as he was growing up. While he eventually opted to write in English, being a writer based in New York, he did clearly consider writing in French, as revealed by two recently-discovered manuscripts. His fame reached far and wide in French-speaking North America, particularly in Quebec, where some have perceived influences reminiscent of the French-Canadian condition in his life and work.

Article disponible en français : Jack Kerouac, un Canadien errant?

A Franco-American Life’s Path

Between 1840 and 1930, more than 900,000 French-speakers left Quebec to settle in the United States, primarily for economic reasons. What started out as seasonal migration turned into permanent emigration with the industrial development of New England, most especially in textile and shoemaking plants that were hiring unskilled labourers (NOTE 1). Despite an active propaganda campaign by the province’s Catholic clergy, who feared that Quebeckers’ faith would be eroded by contact with Americans, numerous families from all over Quebec took to the road and headed south to the United States. Migratory movements were facilitated in particular by development of transportation infrastructures such as the railroads.

It was in this context, at the end of the 19th century, that Jack Kerouac’ grandparents left the Bas-Saint-Laurent (Lower Saint Lawrence) region in search of a brighter future. Jack’s father, Léon-Alcide “Léo” Kerouac, was born in 1889 in Saint-Hubert, a small town located some 30 kilometres from Rivière-du-Loup. His mother, Gabrielle-Ange Lévesque, came into the world in 1894 in Saint-Pacôme. Soon after the birth of these children, both families left the Bas-Saint-Laurent region to settle in Nashua, New Hampshire. This is where Léo and Gabrielle-Ange would meet, court and, on 25 October 1915, marry. The couple then moved to Lowell, Massachusetts, located 45 kilometres north of Boston. Léo Kerouac worked as a printer for the Franco-American newspaper L’Étoile (NOTE 2).

It was in Lowell that Jean-Louis Lebris Kerouac was born, on 12 March 1922—the firstborn in a family of three children. Like many expatriate ethnic groups, Franco-Americans who had settled in Lowell gravitated to a cluster of neighbourhoods referred to as “Petit Canada,” where their demographic concentration was dense enough that they were able to maintain French usage for a time. Jack Kerouac would thus spend the first six years of his life speaking nothing but French in the neighbourhoods of Centralville and Pawtucketville in the orbit of Saint Louis de France church. His playmates’ family names were Beaulieu, Fournier, Bertrand or Houde (NOTE 3). Assimilation nonetheless presented a constant threat, aided and abetted by a superior school system and a more favourable job market. Jack Kerouac left Lowell in 1938, at the age of 16, with a sports scholarship to study at Columbia University in New York. This is where he would come into his vocation as a writer.

An Ambitious Oeuvre

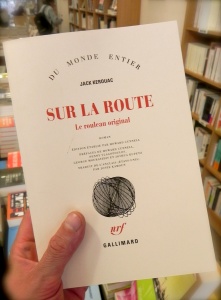

After a few years of balancing short-term jobs, writing, and the exigencies of a Bohemian existence, Jack Kerouac got the first significant break of his literary career in 1950 with the publication of his first novel, The Town and the City. But it was the publication of On the Road in 1957 that catapulted Kerouac to instant nationwide success. Countless readers of On the Road would identify with its heroes’ quest for freedom and would recognize the originality of the author’s spontaneous, syncopated writing technique, evidenced by the sheer speed with which this novel was written. Kerouac, feeding a long, continuous roll of paper into his typewriter, hammered out the complete manuscript in a three-week period from April 2 to April 22, 1951. The version that was eventually published, however—after a few rejections—had been edited, with numerous passages cut from the original manuscript. Readers would have to wait until 2010 to read the original paper-roll version, published in its French translation by Gallimard.

In the manner of Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu, Jack Kerouac envisioned his literary oeuvre as one single, overarching cycle, which he called The Duluoz Legend, made up of 14 individual works that originally recounted the adventures of the same characters. Publishers, however, refused to leave the names of the main characters unchanged from one novel to the next. The traces of his Franco-American experience make up the material of several of his novels, among them The Town and the City, Maggie Cassidy, and Vanity of Duluoz, but more specifically Doctor Sax and Visions of Gerard.

Writing in the Lingo of the Beat Generation and in...Joual

One might be tempted to think, being that Kerouac’s work was published exclusively in English, that the French language was for the writer a memory of his youth that was of no particular importance. However, the discovery by the newspaper Le Devoir in 2007–2008 of two manuscripts written in French by Jack Kerouac in the early 1950s, shed new light on his writing process.

In 2007, an unpublished manuscript of 56 pages entitled La nuit est ma femme, written between February and March of 1951—so, before On the Road—was found by the Quebec daily at the New York Public Library (NOTE 4). A year later, Le Devoir unearthed a novella (about 50 pages long) entitled Sur le chemin, which was written in Mexico City in December of 1952. According to journalist Gabriel Anctil, in this manuscript, “Kerouac transforms the French language, fits it to his own hand, changes the spelling of some words and makes up others to create a musical and playful joual that appears in many ways to be unique in French-language literature” (NOTE 5). This style is comparable that of the novels that he wrote in English.

The project to write in French, then, was quite real for Kerouac at the beginning of the 1950s. But this lingo—this joual of his own invention—was certainly not in line with the tastes of the time in the world of French-language literature. In Quebec, it was not until the 1960s that under the influence of the literary review Parti pris and the early plays of Michel Tremblay, this style would be truly accepted, albeit with its share of detractors. In France, the reception of such lowbrow language was no doubt even chillier. In this context, for a Franco-American, the choice to write in English opened a much broader spectrum of opportunities.

The Condition of French-Speakers in North America

The French translation of Jack Kerouac’s novel, Sur la route, first published by Gallimard in 1960, like the English original On the Road, became required reading for generations of Quebecois and other North American French-speakers (NOTE 6). In Quebec, authors, literary critics, and singers often attempted to establish a connection between the author and the Quebecois (or francophone) condition, and many drew inspiration from his life, his style, and his written work.

The question of Jack Kerouac’s Québécitude gave rise to a particularly lively debate in the1970s. Analyses vacillated between admiration for the avant-garde American writer and criticism tinged with scorn for the “vieux mon-oncle des États” (old fogey from the States) (NOTE 7) who had come from a Catholic background and who wrote in a somewhat outmoded fashion that readers no longer wished to identify with. This position remained current among many Quebecois intellectuals who had rejected the values of the Quebec that existed before the Quiet Revolution. This hiatus, indeed this malaise, were brought to the fore with particular clarity with Jack Kerouac’s appearance on the program Le Sel de la semaine hosted by par Fernand Séguin and broadcast on Radio Canada Television on 7 March 1967. The alcoholic Kerouac appeared old beyond his years, out of sync with his surroundings, and wearing “un air de bûcheron” (the look of a lumberjack) (NOTE 8) as he took part in a discussion in French that, it was said, was preceded by a pub-crawl through a few of Montreal’s drinking establishments.

Having witnessed this debate, the novelist Jean-Marie Poupart, in a 1975 article for Le Devoir, made the categorical statement that there was absolutely nothing Quebecois about Jack Kerouac (NOTE 9). In 1972, the author Victor-Lévy Beaulieu devoted a piece to Kerouac entitled Jack Kerouac : un essai-poulet (NOTE 10), a book that left its mark on the body of studies written on this author’s work. In this essay, Beaulieu presented the contradictions of Kerouac’s character, divided between “backward-looking French Canada and the forward-looking American.” He went even farther, calling, despite the character’s “provincialism,” for the repatriation of Jack Kerouac into Quebecois literature, calling Kerouac “French-Canada’s best writer of powerlessness” (NOTE 11). More or less in this vein is the song Kerouac written in 1978 by composer-songwriter Sylvain Lelièvre. Despite an unmistakeable admiration for the author that is evident in the song, it presents Kerouac as the embodiment, in his capacity as a Franco-American, of the process of assimilation undergone by Quebeckers who had emigrated to the United States.

Kerouac’s Artistic and Literary Legacy

In the1980s, with Quebec mired in post-referendum doldrums, a renewed interest in Jack Kerouac found expression in literature and popular songs. His influence is particularly evident in Jacques Poulin’s Volkswagen Blues (NOTE 12), a bestselling novel published in 1984 in which the main character travels from Gaspésie to California in a VW Minibus. In Poulin’s novel, a journey of initiation—which resembles the journey in Kerouac’s On the Road in many ways—gives readers a chance to recall a time when North America, expanding westward along trails blazed by explorers and intrepid voyageurs, was largely French. In the same spirit, let us mention two songs—L’Ange vagabond by Richard Séguin (1988) and Sur la route by Pierre Flynn (1987).

But it was in a more underground literature that Jack Kerouac was most often emulated, particularly by Beat poets like Patrice Desbiens, Josée Yvon, and Denis Vanier. In this raw, urban, seedy poetry, we find a desire to use a “sub-proletarian joual” to depict a working-class setting (NOTE 13). And until quite recently, the journal Steak Haché, founded by Denis Vanier, kept a stream of this Kerouac-inspired poetry going, with a new generation of young authors taking up the calling. Franco-Ontarian poet Patrice Desbiens, in addition to his poetry writing, wrote words for Quebec’s singers, among them Chloé Sainte-Marie.

A Wandering Canadian?

The “Rencontre internationale Jack Kerouac,” held in Quebec City in 1987, provided an opportunity to assess the French-Canadian individuality of the famous author. Quebeckers, Franco-Americans, Americans, and Franco-Ontarians gave arguments in support of considering Kerouac as one of their own. True, his oeuvre, as suggested by the title of the gathering, was situated “at the crossroads of many cultures,” each of which participated in its own way in forming Jack Kerouac. Should we then accept, on the strength of these arguments vaunting the richness brought by mixing cultures, to “persuade a nation that it can very well live out its culture without its own language?” (NOTE 14). No doubt there is still a French North America where this human cultural diversity lives on. Otherwise, Jack Kerouac, a distinctive literary voice with such a personal style, would remain nothing more than a simple “wandering Canadian, banished from the hearths of his homeland” and living in a “foreign land.”

Christian

Harvey

Historian and researcher at the Centre de

recherche sur l’histoire et le patrimoine de Charlevoix (Centre for

Research on the History and Heritage of Charlevoix)

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

«Sur la route» (Le Ro

«Sur la route» (Le Ro

uleau original)... -

Allen Ginsberg, grand

Allen Ginsberg, grand

ami de Jack Ke... -

Carte présentant le t

Carte présentant le t

rajet emprunté ... -

Chapeau de Jack Kerou

Chapeau de Jack Kerou

ac et édition o...

-

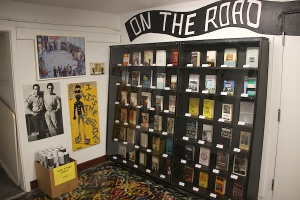

Diverses éditions de

Diverses éditions de

«Sur la route»,... -

Exposition sur Jack K

Exposition sur Jack K

erouac, 2007 -

Fragment du manuscrit

Fragment du manuscrit

de «On the Roa... -

Jack Kerouac

Jack Kerouac

-

Jack Kerouac arborant

Jack Kerouac arborant

une casquette ... -

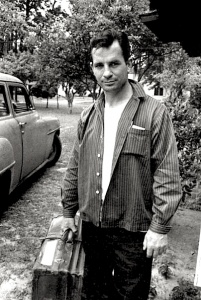

Jack Kerouac en Flori

Jack Kerouac en Flori

da, 1958 -

Jack Kerouac et son c

Jack Kerouac et son c

hat en 1956 -

Jack Kerouac, gravure

Jack Kerouac, gravure

sur bois, 2009

-

Livres de Jack Keroua

Livres de Jack Keroua

c ou portant su... -

Maison où Jack Keroua

Maison où Jack Keroua

c a habité avec... -

Maison où naquit Jack

Maison où naquit Jack

Kerouac, situé... -

Manuscrit de «On the

Manuscrit de «On the

Road» (Sur la r...

-

Photographie de Jack

Photographie de Jack

Kerouac publiée... -

Plaque du lieu-dit de

Plaque du lieu-dit de

Kervoac près d... -

Plaque indiquant la r

Plaque indiquant la r

ue Jack Kerouac... -

Rue Jack Kerouac, 200

Rue Jack Kerouac, 200

9

Documents PDF

-

Rémi Ferland, «Les enjeux de la Rencontre Internationale Jack Kerouac», Voix et images, vol 13, no 3 (1988), p. 422-425.

Rémi Ferland, «Les enjeux de la Rencontre Internationale Jack Kerouac», Voix et images, vol 13, no 3 (1988), p. 422-425.

-

Susan Pinette, «Jack Kerouac: l'écriture et l'identité Franco-Américaine», Francophonies d'Amerique, no 17 (2004), p. 35-43.

Susan Pinette, «Jack Kerouac: l'écriture et l'identité Franco-Américaine», Francophonies d'Amerique, no 17 (2004), p. 35-43.

Hyperliens

- Québec Kerouac Blues - compte rendu de la Rencontre Internationale Jack Kerouac à Québec en 1987

- Le Grand Jack, un docufiction d'Herménégilde Chiasson, ONF, 1987, 54 min 39 s

- Sure la langue de Kerouac, un article de Jean-Sébastien Ménard portant sur le dilemme linguistique de Kerouac, paru dans Canadian Literature

Catégories

Notes

NOTES

1. Paul-André Linteau et al., Histoire du Québec contemporain : De la Confédération à la crise, Montréal, Boréal Express, 1979, p. 41.

2. Gabriel Anctil, “Kerouac, le français et le Québec,” Le Devoir, 8 September 2007.

3. Yves Buin, Kerouac, Paris, Gallimard, 2006, p. 27.

4. Gabriel Anctil, “Les 50 ans d’On the Road – Kerouac voulait écrire en français,” Le Devoir, 5 September 2007.

5. Gabriel Anctil, “Sur le chemin – Découverte d'un deuxième roman en français de Jack Kerouac,” Le Devoir, 4 September 2008.

6. On this topic, for the period 1960–1987, cf. Rod Anstee, Maurice Poteet and Hélène Bédard, “Bibliographie de Jack Kerouac,” in Voix et images, 13, 3 (39), 1988 : 426–434.

7. Words from the song Kerouac by Sylvain Lelièvre.

8. Another quotation taken from the song by Sylvain Lelièvre.

9. Jean-Marie Poupart, “Rien de québécois chez le romancier Jack Kerouac,” Le Devoir, 8 February 1975, p. 16.

10. Victor-Lévy Beaulieu, Jack Kérouac : un essai-poulet, Montreal, Éditions du Jour, 1972. 235 p. Translation: Jack Kerouac: A Chicken-Essay, translated by Sheila Fischman, Toronto, Coach House Press, c1975, 170 p.

11. Michel Lapierre. “Le ciel de Kerouac, la terre de VLB,” Le Devoir, 21 February 2004.

12. Jacques Poulin. Volkswagen Blues, Montreal, Québec/Amérique, 1984. 290 p.

13. Denis Vanier, “La marginalisation de Jack Kerouac par la Beat Generation,” in Pierre Anctil et al. Un Homme grand : Jack Kerouac at the Crossroads of Many Cultures / Jack Kerouac à la confluence des cultures. Carleton, Carleton University Press, 1990. pp. 115–123.

14. Rémi Ferland. “Les enjeux de la Rencontre international Jack Kerouac,” Voix et images, 13, 3 (39), 1988: 422–425.